Tuples, Files and Everything Else

Tuples

Tuples construct simple groups of objects. They work exactly like lists, except that tuples can’t be changed in place (they’re immutable) and are usually written as a series of items in parentheses, not square brackets.

Python tuples are :

- Ordered collections of arbitrary objects.

- Accessed by offset.

- Fixed-length, heterogeneous, and arbitrarily nestable.

- Of the category “immutable sequence”.

- Arrays of object references.

Common tuple literals and operations :

| Operation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| () | Empty tuple |

| T = (0,) | A 1 item tuple |

| T = (0, ‘Ni’, 1.2, 3) | A 4 item tuple |

| T = (‘Bob’, (‘dev’, ‘mgr’)) | Nested tuples |

| T[i] | Index |

| T1 + T2 | Concatenate |

| for x in T: print(x) | Iteration |

Tuples in Action

Tuples do not have all the methods that lists have (e.g., an append call won’t work here). They do, however, support the usual sequence operations that we saw for both strings and lists:

>>> (1, 2) + (3, 4) # Concatenation

(1, 2, 3, 4)

>>> (1, 2) * 4 # Repetition

(1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2)

>>> T = (1, 2, 3, 4) # Indexing, slicing

>>> T[0], T[1:3]

(1, (2, 3))

Python also allows you to omit the opening and closing parentheses for a tuple in contexts where it isn’t syntactically ambiguous to do so. The only differences worth noting are that the +, *, and slicing operations return new tuples when applied to tuples, and that tuples don’t provide the same methods you saw for strings, lists, and dictionaries. If you want to sort a tuple, for example, you’ll usually have to either first convert it to a list to gain access to a sorting method call and make it a mutable object, or use the newer sorted built-in that accepts any sequence object.

>>> T = ('cc', 'aa', 'dd', 'bb')

>>> tmp = list(T) # Make a list from a tuple's items

>>> tmp.sort() # Sort the list

>>> tmp

[‘aa’, ‘bb’, ‘cc’, ‘dd’]

>>> T = tuple(tmp) # Make a tuple from the list's items

>>> T

(‘aa’, ‘bb’, ‘cc’, ‘dd’)

>>> sorted(T) # Or use the sorted built-in, and save two steps

[‘aa’, ‘bb’, ‘cc’, ‘dd’]

Why Lists and Tuples?

The best answer, is that the immutability of tuples provides some integrity—you can be sure a tuple won’t be changed through another reference elsewhere in a program, but there’s no such guarantee for lists. Tuples and other immutables, therefore, serve a similar role to “constant” declarations in other languages, though the notion of constantness is associated with objects in Python, not variables.

Named Tuples

With a bit of extra work, we can implement objects that offer both positional and named access to record fields. For example, the namedtuple utility, available in the standard library’s collections module mentioned in Chapter 8, implements an extension type that adds logic to tuples that allows components to be accessed by both position and attribute name, and can be converted to dictionary-like form for access by key if desired. Attribute names come from classes and are not exactly dictionary keys, but they are similarly mnemonic :

>>> from collections import namedtuple # Import extension type

>>> Rec = namedtuple('Rec', ['name', 'age', 'jobs']) # Make a generated class

>>> bob = Rec('Bob', age=40.5, jobs=['dev', 'mgr']) # A named-tuple record

>>> bob

Rec(name=’Bob’, age=40.5, jobs=[‘dev’, ‘mgr’])

>>> bob[0], bob[2] # Access by position

(‘Bob’, [‘dev’, ‘mgr’])

>>> bob.name, bob.jobs # Access by attribute

(‘Bob’, [‘dev’, ‘mgr’])

As you can see, named tuples are a tuple/class/dictionary hybrid. They also represent a classic tradeoff. In exchange for their extra utility, they require extra code (the two startup lines in the preceding examples that import the type and make the class), and incur some performance costs to work this magic.

Files

You may already be familiar with the notion of files, which are named storage compartments on your computer that are managed by your operating system. The built-in open function creates a Python file object, which serves as a link to a file residing on your machine. After calling open, you can transfer strings of data to and from the associated external file by calling the returned file object’s methods.

Common file operations :

| Operation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| output = open(r’C:\spam’, ‘w’) | Create output file (‘w’ means write) |

| input = open(‘data’, ‘r’) | Create input file (‘r’ means read) |

| aString = input.read() | Read entire file into a single string |

| aString = input.readline() | Read next line (including \n newline) into a string |

| output.write(aString) | Write a string of characters (or bytes) into file |

| output.close() | Manual close (done for you when file is collected) |

| output.flush() | Flush output buffer to disk without closing |

| anyFile.seek(N) | Change file position to offset N for next operation |

| for line in open(‘data’): use line | File iterators read line by line |

Opening Files

To open a file, a program calls the built-in open function, with the external filename first, followed by a processing mode. The call returns a file object, which in turn has methods for data transfer :

afile = open(filename, mode)

afile.method()

The first argument to open, the external filename, may include a platform-specific and absolute or relative directory path prefix. Without a directory path, the file is assumed to exist in the current working directory (i.e., where the script runs). The second argument to open, processing mode, is typically the string ‘r’ to open for text input (the default), ‘w’ to create and open for text output, or ‘a’ to open for appending text to the end (e.g., for adding to logfiles).

Using Files

Once you make a file object with open, you can call its methods to read from or write to the associated external file. In all cases, file text takes the form of strings in Python programs; reading a file returns its content in strings, and content is passed to the write methods as strings. Here are a few fundamental usage notes :

- File iterators are best for reading lines.

- Content is strings, not objects.

- Files are buffered and seekable.

- Close is often optional: auto-close on collection.

Files in Action

Let’s work through a simple example that demonstrates file-processing basics. The following code begins by opening a new text file for output, writing two lines (strings terminated with a newline marker, \n), and closing the file. Later, the example opens the same file again in input mode and reads the lines back one at a time with read line.

>>> myfile = open('myfile.txt', 'w') # Open for text output: create/empty

>>> myfile.write('hello text file\n') # Write a line of text: string

16

>>> myfile.write('goodbye text file\n')

18

>>> myfile.close() # Flush output buffers to disk

>>> myfile = open('myfile.txt') # Open for text input: 'r' is default

>>> myfile.readline() # Read the lines back

‘hello text file\n’

>>> myfile.readline()

‘goodbye text file\n’

And if you want to scan a text file line by line, file iterators are often your best option :

>>> for line in open('myfile.txt'): # Use file iterators, not reads

... print(line, end='')

...

hello text file goodbye text file

Text and Binary Files : The short story

Python has always supported both text and binary files, but in Python 3.X there is a sharper distinction between the two:

- Text files represent content as normal str strings, perform Unicode encoding and decoding automatically, and perform end-of-line translation by default.

- Binary files represent content as a special bytes string type and allow programs to access file content unaltered.

When you read a binary data file you get back a bytes object—a sequence of small integers that represent absolute byte values (which may or may not correspond to characters), which looks and feels almost exactly like a normal string. In Python 3.X, and assuming an existing binary file :

>>> data = open('data.bin', 'rb').read() # Open binary file: rb=read binary

>>> data # bytes string holds binary data

b’\x00\x00\x00\x07spam\x00\x08’

>>> data[4:8] # Act like strings

b’spam’

>>> data[4:8][0] # But really are small 8-bit integers

115

Storing Python Objects in Files: Conversions

Our next example writes a variety of Python objects into a text file on multiple lines. Notice that it must convert objects to strings using conversion tools.

>>> X, Y, Z = 43, 44, 45 # Native Python objects

>>> S = 'Spam' # Must be strings to store in file

>>> D = {'a': 1, 'b': 2}

>>> L = [1, 2, 3]

>>>

>>> F = open('datafile.txt', 'w') # Create output text file

>>> F.write(S + '\n') # Terminate lines with \n

>>> F.write('%s,%s,%s\n' % (X, Y, Z)) # Convert numbers to strings

>>> F.write(str(L) + '$' + str(D) + '\n') # Convert and separate with $

>>> F.close()

Once we have created our file, we can inspect its contents by opening it and reading it into a string (strung together as a single operation here).

>>> chars = open('datafile.txt').read() # Raw string display

>>> chars

“Spam\n43,44,45\n[1, 2, 3]${‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 2}\n”

>>> print(chars) # User-friendly display

Spam 43,44,45 [1, 2, 3]${‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 2}

Now let’s grab the next line, which contains numbers, and parse out (that is, extract) the objects on that line:

>>> line = F.readline() # Next line from file

>>> line # It's a string here

‘43,44,45\n’

>>> parts = line.split(',') # Split (parse) on commas

>>> parts

[‘43’, ‘44’, ‘45\n’]

Storing Native Python Objects : pickle

The pickle module is a more advanced tool that allows us to store almost any Python object in a file directly, with no to- or from-string conversion requirement on our part. It’s like a super-general data formatting and parsing utility. To store a dictionary in a file, for instance, we pickle it directly :

>>> D = {'a': 1, 'b': 2}

>>> F = open('datafile.pkl', 'wb')

>>> import pickle

>>> pickle.dump(D, F) # Pickle any object to file

>>> F.close()

Then, to get the dictionary back later, we simply use pickle again to re-create it:

>>> F = open('datafile.pkl', 'rb')

>>> E = pickle.load(F) # Load any object from file

>>> E

{‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 2}

The pickle module performs what is known as object serialization—converting objects to and from strings of bytes—but requires very little work on our part. In fact, pickle internally translates our dictionary to a string form, though it’s not much to look at (and may vary if we pickle in other data protocol modes) :

>>> open('datafile.pkl', 'rb').read() # Format is prone to change!

b’\x80\x03}q\x00(X\x01\x00\x00\x00bq\x01K\x02X\x01\x00\x00\x00aq\x02K\x01u.’

Storing Python Objects in JSON Format

JSON is a newer and emerging data interchange format, which is both programming-language-neutral and supported by a variety of systems. MongoDB, for instance, stores data in a JSON document database. JSON does not support as broad a range of Python object types as pickle, but its portability is an advantage in some contexts, and it represents another way to serialize a specific category of Python objects for storage and transmission. Moreover, because JSON is so close to Python dictionaries and lists in syntax, the translation to and from Python objects is trivial, and is automated by the json standard library module.

>>> name = dict(first='Bob', last='Smith')

>>> rec = dict(name=name, job=['dev', 'mgr'], age=40.5)

>>> rec

{‘job’: [‘dev’, ‘mgr’], ‘name’: {‘last’: ‘Smith’, ‘first’: ‘Bob’}, ‘age’: 40.5}

The final dictionary format displayed here is a valid literal in Python code, and almost passes for JSON when printed as is, but the json module makes the translation official —here translating Python objects to and from a JSON serialized string representation in memory :

>>> import json

>>> json.dumps(rec)

’{“job”: [“dev”, “mgr”], “name”: {“last”: “Smith”, “first”: “Bob”}, “age”: 40.5}’

>>> S = json.dumps(rec)

>>> S

’{“job”: [“dev”, “mgr”], “name”: {“last”: “Smith”, “first”: “Bob”}, “age”: 40.5}’

>>> O = json.loads(S)

>>> O

{‘job’: [‘dev’, ‘mgr’], ‘name’: {‘last’: ‘Smith’, ‘first’: ‘Bob’}, ‘age’: 40.5}

>>> O == rec

True

Other File Tools

The open function and the file objects it returns are your main interface to external files in a Python script, there are additional file-like tools in the Python toolset. Among these :

- Standard streams

- Descriptor files in the os module

- Sockets, pipes, and FIFOs

- Access-by-key files known as “shelves”

- Shell command streams

Core Types Review and Summary

Here are some points to remember :

- Objects share operations according to their category; for instance, sequence objects—strings, lists, and tuples—all share sequence operations such as concatenation, length, and indexing.

- Only mutable objects—lists, dictionaries, and sets—may be changed in place; you cannot change numbers, strings, or tuples in place.

- Files export only methods, so mutability doesn’t really apply to them—their state may be changed when they are processed, but this isn’t quite the same as Python core type mutability constraints.

- Sets are something like the keys of a valueless dictionary, but they don’t map to values and are not ordered, so sets are neither a mapping nor a sequence type; frozenset is an immutable variant of set.

Object Classification :

| Object type | Category | Mutable? |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers (all) | Numeric | No |

| Strings (all) | Sequence | No |

| Lists | Sequence | Yes |

| Dictionaries | Mapping | Yes |

| Tuples | Sequence | No |

| Files | Extension | N/A |

| Sets | Set | Yes |

| Frozenset | Set | No |

| bytearray | Sequence | Yes |

Object flexibility in general :

- Lists, dictionaries, and tuples can hold any kind of object.

- Sets can contain any type of immutable object.

- Lists, dictionaries, and tuples can be arbitrarily nested.

- Lists, dictionaries, and sets can dynamically grow and shrink.

Comparisons, Equality, and Truth

All Python objects also respond to comparisons: tests for equality, relative magnitude, and so on. Python comparisons always inspect all parts of compound objects until a result can be determined. In fact, when nested objects are present, Python automatically traverses data structures to apply comparisons from left to right, and as deeply as needed. The first difference found along the way determines the comparison result.

>>> L1 = [1, ('a', 3)] # Same value, unique objects

>>> L2 = [1, ('a', 3)]

>>> L1 == L2, L1 is L2 # Equivalent? Same object?

(True, False)

Here, L1 and L2 are assigned lists that are equivalent but distinct objects. As a review of what we saw in Chapter 6, because of the nature of Python references, there are two ways to test for equality :

- The == operator tests value equivalence. Python performs an equivalence test, comparing all nested objects recursively.

- The is operator tests object identity. Python tests whether the two are really the same object (i.e., live at the same address in memory).

Notice what happens for short strings, though:

>>> S1 = 'spam'

>>> S2 = 'spam'

>>> S1 == S2, S1 is S2

(True, True)

Here, we should again have two distinct objects that happen to have the same value: == should be true, and is should be false. But because Python internally caches and reuses some strings as an optimization, there really is just a single string ‘spam’ in memory, shared by S1 and S2; hence, the is identity test reports a true result. To trigger the normal behavior, we need to use longer strings :

>>> S1 = 'a longer string'

>>> S2 = 'a longer string'

>>> S1 == S2, S1 is S2

(True, False)

More specifically, Python compares types as follows :

- Numbers are compared by relative magnitude, after conversion to the common highest type if needed.

- Strings are compared lexicographically (by the character set code point values returned by ord), and character by character until the end or first mismatch (“abc”< “ac”).

- Lists and tuples are compared by comparing each component from left to right, and recursively for nested structures, until the end or first mismatch ([2] > [1, 2]).

- Sets are equal if both contain the same items (formally, if each is a subset of the other), and set relative magnitude comparisons apply subset and superset tests.

- Dictionaries compare as equal if their sorted (key, value) lists are equal. Relative magnitude comparisons are not supported for dictionaries in Python 3.X, but they work in 2.X as though comparing sorted (key, value) lists.

- Nonnumeric mixed-type magnitude comparisons (e.g., 1 < ‘spam’) are errors in Python 3.X.

The Meaning of True and False in Python

Notice that the test results returned in the last two examples represent true and false values. They print as the words True and False. Python recognizes any empty data structure as false and any nonempty data structure as true. More generally, the notions of true and false are intrinsic properties of every object in Python—each object is either true or false, as follows :

- Numbers are false if zero, and true otherwise.

- Other objects are false if empty, and true otherwise.

Python also provides a special object called None, which is always considered to be false. Keep in mind that None does not mean “undefined.” That is, None is something, not nothing (despite its name!)—it is a real object and a real piece of memory that is created and given a built-in name by Python itself. The built-in words True and False are just customized versions of the integers 1 and 0—it’s as if these two words have been preassigned to 1 and 0 everywhere in Python. Because of the way this new type is implemented, this is really just a minor extension to the notions of true and false already described, designed to make truth values more explicit :

- When used explicitly in truth test code, the words True and False are equivalent to 1 and 0, but they make the programmer’s intent clearer.

- Results of Boolean tests run interactively print as the words True and False, instead of as 1 and 0, to make the type of result clearer.

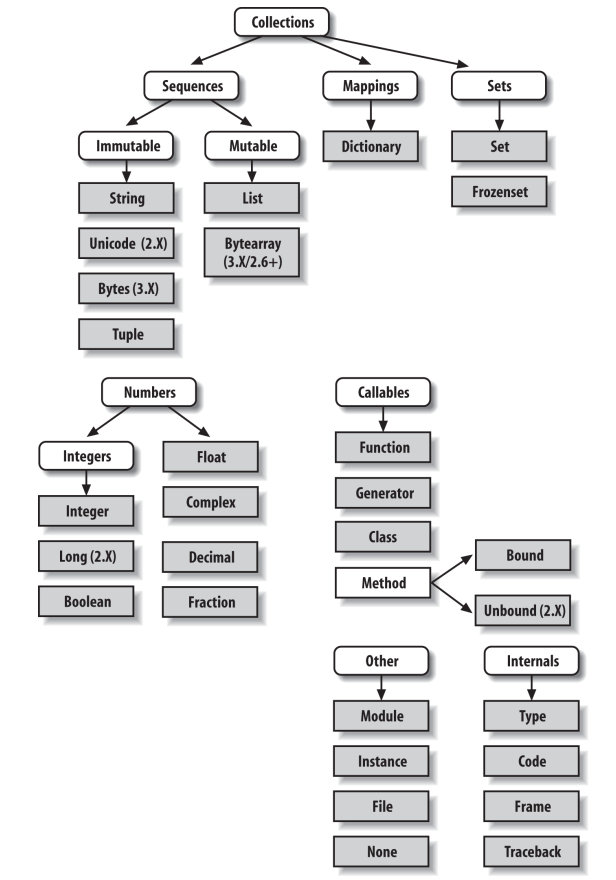

Python’s Type Hierarchies

The largest point to notice here is that everything in a Python system is an object type and may be processed by your Python programs. For instance, you can pass a class to a function, assign it to a variable, stuff it in a list or dictionary, and so on.

Built-in Type Gotchas

Some common problems that seem to trap new users :

- Assignment Creates References, Not Copies.

- Repetition Adds One Level Deep.

- Beware of Cyclic Data Structures.

- Immutable Types Can’t Be Changed in Place.

Test Your Knowledge

Q1 - How can you determine how large a tuple is? Why is this tool located where it is?

The built-in len function returns the length (number of contained items) for any container

object in Python, including tuples. It is a built-in function instead of a type method

because it applies to many different types of objects. In general, built-in functions and

expressions may span many object types; methods are specific to a single object type,

though some may be available on more than one type (index, for example, works on lists

and tuples).

Q2 - Write an expression that changes the first item in a tuple. (4, 5, 6) should become (1, 5, 6) in the process.

Because they are immutable, you can’t really change tuples in place, but you can

generate a new tuple with the desired value. Given T = (4, 5, 6), you can change the

first item by making a new tuple from its parts by slicing and concatenating: T = (1,)

+ T[1:]. (Recall that single-item tuples require a trailing comma.) You could also

convert the tuple to a list, change it in place, and convert it back to a tuple, but

this is more expensive and is rarely required in practice—simply use a list if you

know that the object will require in-place changes.

Q3 - What is the default for the processing mode argument in a file open call?

The default for the processing mode argument in a file open call is 'r', for reading text

input. For input text files, simply pass in the external file’s name.

Q4 - What module might you use to store Python objects in a file without converting them to strings yourself?

The pickle module can be used to store Python objects in a file without explicitly

converting them to strings. The struct module is related, but it assumes the data is to

be in packed binary format in the file; json similarly converts a limited set of Python

objects to and from strings per the JSON format.

Q5 - How might you go about copying all parts of a nested structure at once?

Import the copy module, and call copy.deepcopy(X) if you need to copy all parts of a

nested structure X. This is also rarely seen in practice; references are usually the

desired behavior, and shallow copies (e.g., aList[:], aDict.copy(), set(aSet)) usually

suffice for most copies.

Q6 - When does Python consider an object true?

An object is considered true if it is either a nonzero number or a nonempty collection

object. The built-in words True and False are essentially predefined to have the same

meanings as integer 1 and 0, respectively.

Q7 - What is your quest?

Acceptable answers include “To learn Python,”.

Test Your Knowledge - Exercises

Q1 - The basics

>>> 2 ** 16 # 2 raised to the power 16

65536

Q2 - Indexing and Slicing

>>> L = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> L[4]

Traceback (innermost last): File “

", line 1, in ? IndexError: list index out of range

Q3 - del

>>> del L[0]

>>> L

[2, 3, 4]

Q4 - Tuple assignment

>>> X = 'spam'

>>> Y = 'eggs'

>>> X, Y = Y, X

>>> X

‘eggs’

>>> Y

‘spam’

Q5 - Dictionary Keys

>>> D = {}

>>> D[1] = 'a'

>>> D[2] = 'b'

>>> D[(1, 2, 3)] = 'c'

>>> D

{1: ‘a’, 2: ‘b’, (1, 2, 3): ‘c’}

Q6 - Dictionary indexing

>>> D = {'a':1, 'b':2, 'c':3}

>>> D['a']

1

Q7 - Generic operations

1. The + operator doesn’t work on different/mixed types (e.g., string + list, list

+ tuple).

2. + doesn’t work for dictionaries, as they aren’t sequences.

3. The append method works only for lists, not strings, and keys works only on

dictionaries. append assumes its target is mutable, since it’s an in-place extension;

strings are immutable.

4. Slicing and concatenation always return a new object of the same type as the

objects processed.

Q8 - String indexing

>>> S = "spam"

>>> S[0][0][0][0][0]

’s’

Q9 - Immutable types

>>> S = "spam"

>>> S = S[0] + 'l' + S[2:]

>>> S

‘slam’

Q10 - Nesting

>>> me = {'name':('John', 'Q', 'Doe'), 'age':'?', 'job':'engineer'}

>>> me['job']

‘engineer’

Q11 - Files

# File: maker.py

file = open('myfile.txt', 'w')

file.write('Hello file world!\n') # Or: open().write()

file.close() # close not always needed