Naive Bayes and Sentiment Classification

Classification lies at the heart of both human and machine intelligence. Deciding what letter, word, or image has been presented to our senses, recognizing faces or voices, sorting mail, assigning grades to homeworks; these are all examples of assigning a category to an input. The goal of classification is to take a single observation, extract some useful features, and thereby classify the observation into one of a set of discrete classes.

We focus on one common text categorization task, sentiment analysis, the ex- sentiment analysis traction of sentiment, the positive or negative orientation that a writer expresses toward some object. A review of a movie, book, or product on the web expresses the author’s sentiment toward the product, while an editorial or political text expresses sentiment toward a candidate or political action. Spam detection is another important commercial application, the binary classification task of assigning an email to one of the two classes spam or not-spam. Many lexical and other features can be used to perform this classification.

Naive Bayes Classifiers

We introduce the multinomial naive Bayes classifier, so called because it is a Bayesian classifier that makes a simplifying (naive) assumption about how the features interact. We represent a text document bag of words as if it were a bag of words, that is, an unordered set of words with their position ignored, keeping only their frequency in the document. For example instead of representing the word order in all the phrases like “I love this movie” and “I would recommend it”, we simply note that the word I occurred 5 times in the entire excerpt, the word it 6 times, the words love, recommend, and movie once, and so on.

Naive Bayes is a probabilistic classifier, meaning that for a document d, out of all classes c ∈ C the classifier returns the class ^c which has the maximum posterior probability given the document.

\[\hat c = argmaxP(c|d)\]Using Bayes’ rule :

\[P(x|y)=\frac{P(y|x)P(x)}{P(y)} \\ \hat c = argmax \frac{P(d|c)P(c)}{P(d)}\]We can conveniently simply by dropping the denominator P(d). This is possible because we will be computing it for each possible class. But P(d) doesn’t change for each class; we are always asking about the most likely class for same document d.

\[\hat c = argmax \frac{P(d|c)P(c)}{}\]| To return to classification: we compute the most probable class c given some document d by choosing the class which has the highest product of two probabilities : the prior probability of the class P(c) and the likelihood of the document P(d | c). Without loss of generalization we can represent a document d as a set of features : |

Naive Bayes classifiers make two simplifying assumptions :

- The first is the bag-of-words assumption discussed intuitively above: we assume position doesn’t matter, and that the word “love” has the same effect on classification whether it occurs as the 1st, 20th, or last word in the document. Thus we assume that the features f1, f2,…, fn only encode word identity and not position.

- The second is commonly called the naive Bayes assumption: this is the conditional independence assumption that the probabilities

P(fi|c)are independent given the class c and hence can be ‘naively’ multiplied.

Naive Bayes calculations, like calculations for language modeling, are done in log space, to avoid underflow and increase speed.

\[c_{NB} = argmax logP(c) \sum logP(w_i|c)\]Training the Naive Bayes Classifier

| How can we learn the probabilities P(c) and P(fi | c)? Let’s first consider the maximum likelihood estimate. For the class prior P(c) we ask what percentage of the documents in our training set are in each class c. Let Nc be the number of documents in our training data with class c and Ndoc be the total number of documents. Then : |

| To learn the probability P(fi | c), we’ll assume a feature is just the existence of a word in the document’s bag of words, and so we’ll want P(wi | c), which we compute as the fraction of times the word wi appears among all words in all documents of topic c. |

There is a problem, however, with maximum likelihood training. Imagine we are trying to estimate the likelihood of the word “fantastic” given class positive, but suppose there are no training documents that both contain the word “fantastic” and are classified as positive. Perhaps the word “fantastic” happens to occur (sarcastically?) in the class negative. In such a case the probability for this feature will be zero. The simplest solution is the add-one (Laplace) smoothing :

\[\hat P(w_i|c) = \frac{count(w_i,c)+1}{\sum_{w \in V}(count(w,c)+1)} =\frac{count(w_i,c)+1}{(\sum_{w \in V}count(w,c)) + |V|}\]What do we do about words that occur in our test data but are not in our vocabulary at all because they did not occur in any training document in any class? The solution for such unknown words is to ignore them—remove them from the test document and not include any probability for them at all. Final Algorithm :

function TRAIN NAIVE BAYES(D, C) returns log P(c) and log P(w|c)

for each class c ∈ C # Calculate P(c) terms

N<sub>doc</sub> = number of documents in D

N<sub>c</sub> = number of documents from D in class c

$$ logprior[c]← log \frac{N_c}{N_{doc}} $$

V←vocabulary of D

bigdoc[c]←append(d) for d ∈ D with class c

for each word w in V # Calculate P(w|c) terms

count(w,c)←# of occurrences of w in bigdoc[c]

$$ loglikelihood[w,c]← log \frac{count(w, c) + 1}{\sum_{w^t in V}(count(w^t,c)+1)} $$

return logprior, loglikelihood, V

function TEST NAIVE BAYES(testdoc, logprior, loglikelihood, C, V) returns best c

for each class c ∈ C

sum[c]← logprior[c]

for each position i in testdoc

word←testdoc[i]

if word ∈ V

sum[c]←sum[c]+ loglikelihood[word,c]

return argmax<sub>c</sub>sum[c]

Worked example

Let’s walk through an example of training and testing naive Bayes with add-one smoothing, take the following miniature training and test documents.

| Cat | Documents | |

|---|---|---|

| Training | - | just plain boring |

| Training | - | entirely predictable and lacks energy |

| Training | - | no surprises and very few laughs |

| Training | + | very powerful |

| Training | + | the most fun film of the summer |

| Test | ? | predictable with no fun |

The word with doesn’t occur in the training set, so we drop it completely. Others :

\[P("predictable"|-)=\frac{1+1}{14+20} \\ P("predictable"|+)=\frac{0+1}{9+20} \\ P("no"|-)=\frac{1+1}{14+20} \\ P("no"|+)=\frac{0+1}{9+20} \\ P("fun"|-)=\frac{0+1}{14+20} \\ P("fun"|+)=\frac{1+1}{9+20} \\\]For the test sentence S = “predictable with no fun”, after removing the word ‘with’, the chosen class is :

\[P(-)P(S|-)=\frac{3}{5}* \frac{2*2*1}{34^3}=6.1*10^{-5} \\ P(+)P(S|+)=\frac{2}{5}* \frac{1*1*2}{29^3}=3.2*10^{-5} \\\]The model predicts the class negative for the test sentence.

Optimizing for Sentiment Analysis

Some small changes are generally employed that improve performance.

First, for sentiment classification and a number of other text classification tasks, whether a word occurs or not seems to matter more than its frequency. Thus it often improves performance to clip the word counts in each document at. This variant is called binary multinomial naive Bayes or binary naive Bayes.

A second important addition commonly made when doing text classification for sentiment is to deal with negation. A very simple baseline that is commonly used in sentiment analysis to deal with negation is the following: during text normalization, prepend the prefix NOT to every word after a token of logical negation (n’t, not, no, never) until the next punctuation mark. Thus the phrase didn’t like this movie , but I becomes didn’t NOT_like NOT_this NOT_movie , but I.

Finally, in some situations we might have insufficient labeled training data to train accurate naive Bayes classifiers using all words in the training set to estimate positive and negative sentiment. In such cases we can instead derive the positive and negative word features from sentiment lexicons, lists of words that are preannotated with positive or negative sentiment.

Naive Bayes for other text classification tasks

Consider the task of spam detection, deciding if a particular piece of email is an example of spam. A common solution here, rather than using all the words as individual features, is to predefine likely sets of words or phrases as features, combined with features that are not purely linguistic.

For other tasks, like language id-determining what language a given piece of text is written in-the most effective naive Bayes features are not words at all, but character n-grams, 2-grams (‘zw’) 3-grams (‘nya’, ‘ Vo’), or 4-grams (‘ie z’, ‘thei’), or, even simpler byte n-grams, where instead of using the multibyte Unicode character representations called codepoints, we just pretend everything is a string of raw bytes.

Naive Bayes as language model

Naive Bayes classifiers can use any sort of feature: dictionaries, URLs, email addresses, network features, phrases, and so on. But if, as in the previous section, we use only individual word features, and we use all of the words in the text (not a subset), then naive Bayes has an important similarity to language modeling. Specifically, a naive Bayes model can be viewed as a set of class-specific unigram language models, in which the model for each class instantiates a unigram language model.

Thus consider a naive Bayes model with the classes positive (+) and negative (-) and the following model parameters :

| w | P(w|+) |

P(w|-) |

|---|---|---|

| I | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| love | 0.1 | 0.001 |

| this | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| fun | 0.05 | 0.005 |

| film | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Each of the two columns above instantiates a language model that can assign a probability to the sentence “I love this fun film” :

P(“I love this fun film”|+) = 0.1×0.1×0.01×0.05×0.1 = 0.0000005

P(“I love this fun film”|−) = 0.2×0.001×0.01×0.005×0.1 = .0000000010

Evaluation : Precision, Recall, F-measure

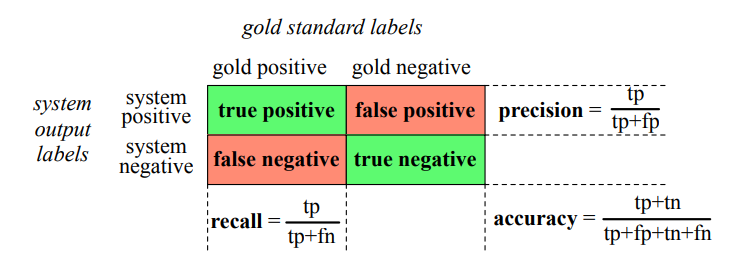

To introduce the methods for evaluating text classification, let’s first consider some simple binary detection tasks. For example, in spam detection, our goal is to label every text as being in the spam category (“positive”) or not in the spam category (“negative”). For each item (email document) we therefore need to know whether our system called it spam or not. We also need to know whether the email is actually spam or not, i.e. the human-defined labels for each document that we are trying to gold labels match. We will refer to these human labels as the gold labels.

To evaluate any system for detecting things, we start by building a confusion matrix. A confusion matrix is a table for visualizing how an algorithm performs with respect to the human gold labels, using two dimensions (system output and gold labels), and each cell labeling a set of possible outcomes. In the spam detection case, for example, true positives are documents that are indeed spam (indicated by human-created gold labels) that our system correctly said were spam. False negatives are documents that are indeed spam but our system incorrectly labeled as non-spam.

Accuracy is not a good metric when the goal is to discover something that is rare, or at least not completely balanced in frequency, which is a very common situation in the world. That’s why instead of accuracy we generally turn to two other metrics shown in precision Fig. 4.4: precision and recall. Precision measures the percentage of the items that the system detected (i.e., the system labeled as positive) that are in fact positive (i.e., are positive according to the human gold labels). Precision is defined as :

\[Precision = \frac{true positives}{true positives + false positives}\]Recall measures the percentage of items actually present in the input that were correctly identified by the system. Recall is defined as :

\[Recall = \frac{true positives}{true positives + false negatives}\]There are many ways to define a single metric that incorporates aspects of both precision and recall. The simplest of these combinations is the F-measure, defined as :

\[F_\beta = \frac{(\beta^2+1)PR}{\beta^2P+R}\]The β parameter differentially weights the importance of recall and precision, based perhaps on the needs of an application. Values of β > 1 favor recall, while values of β < 1 favor precision. When β = 1, precision and recall are equally balF1 anced; this is the most frequently used metric.

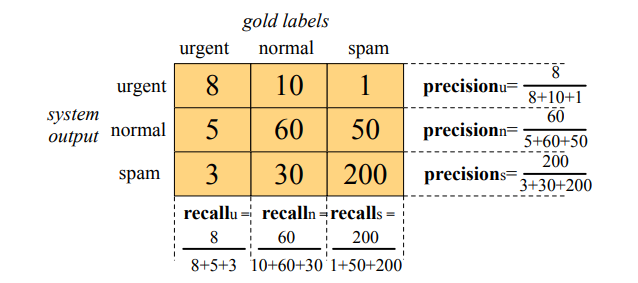

Evaluating with more than two classes

Up to now we have been describing text classification tasks with only two classes. But lots of classification tasks in language processing have more than two classes. For sentiment analysis we generally have 3 classes (positive, negative, neutral).

In order to derive a single metric that tells us how well the system is doing, we can combine these values in two ways. In macroaveraging, we compute the performance for each class, and then average over classes. In microaveraging, we collect the decisions for all classes into a single confusion matrix, and then compute precision and recall from that table.

Test sets and Cross-validation

We use the training set to train the model, then use the development test set (also called a devset) to perhaps tune some parameters, and in general decide what the best model is. While the use of a devset avoids overfitting the test set, having a fixed training set, devset, and test set creates another problem: in order to save lots of data for training, the test set (or devset) might not be large enough to be representative.

In cross-validation, we choose a number k, and partition our data into k disjoint subsets called folds. Now we choose one of those k folds as a test set, train our classifier on the remaining k − 1 folds, and then compute the error rate on the test set. Then we repeat with another fold as the test set, again training on the other k−1 folds. We do this sampling process k times and average the test set error rate from these k runs to get an average error rate. If we choose k = 10, we would train 10 different models (each on 90% of our data), test the model 10 times, and average these 10 values. This is called 10-fold cross-validation.