Overfitting

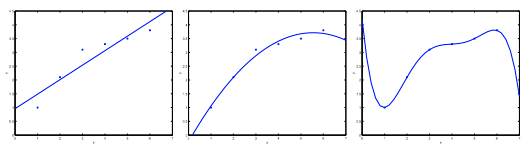

Overfitting is a modeling error in statistics that occurs when a function is too closely aligned to a limited set of data points. As a result, the model is useful in reference only to its initial data set, and not to any other data sets. Overfitting the model generally takes the form of making an overly complex model to explain idiosyncrasies in the data under study. In reality, the data often studied has some degree of error or random noise within it. Thus, attempting to make the model conform too closely to slightly inaccurate data can infect the model with substantial errors and reduce its predictive power. Consider the problem of predicting y from x ∈ R. The leftmost figure below shows the result of fitting a y = θ0 + θ1x to a dataset. We see that the data doesn’t really lie on straight line, and so the fit is not very good.

Instead, if we had added an extra feature x2, and fit y = θ0 + θ1x + θ2x2, then we obtain a slightly better fit to the data (See middle figure). Naively, it might seem that the more features we add, the better. However, there is also a danger in adding too many features: The rightmost figure is the result of fitting a 5th order polynomial. We see that even though the fitted curve passes through the data perfectly, we would not expect this to be a very good predictor of, say, housing prices (y) for different living areas (x). Without formally defining what these terms mean, we’ll say the figure on the left shows an instance of underfitting—in which the data clearly shows structure not captured by the model—and the figure on the right is an example of overfitting. Let’s see how it behaves in Logisitic Regression :

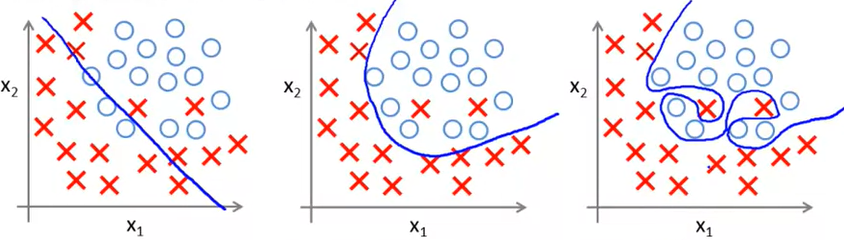

So in logistic regression also we are faced with the same issue. In leftmost figure we see a decision boundary of y = θ0 + θ1x to a dataset. But we see that this straight line is not enough to create the decision boundary and hence it is underfit. Now if we add an extra feature x2, and fit y = θ0 + θ1x + θ2x2 then we get a better decision boundary and it fits slightly better (see middle figure). Now if we try too hard and add more higher order terms it will create a perfect fit decision boundary. And hence we reach to a point of overfitting.

Underfitting, or high bias, is when the form of our hypothesis function h maps poorly to the trend of the data. It is usually caused by a function that is too simple or uses too few features. At the other extreme, overfitting, or high variance, is caused by a hypothesis function that fits the available data but does not generalize well to predict new data. It is usually caused by a complicated function that creates a lot of unnecessary curves and angles unrelated to the data.

Addressing Overfitting

Plotting is not an ideal solution to identify overfitting as in previous graphs we are just working with 1 feature. But our actual problem will contain multiple feature. So it will become impossible to plot on graph. Their are 2 ways to reduce overfitting :

- Reduce the number of features. Either manually select which features to keep or use a model selection algorithm

- Regularization : Keep all the features, but reduce the magnitude of parameters θ. Regularization works well when we have a lot of slightly useful features.

Regularization

The word regularize means to make things regular or acceptable. This is exactly why we use it for. Regularizations are techniques used to reduce the error by fitting a function appropriately on the given training set and avoid overfitting. In previous example we saw that by increasing degree of hypothesis function we overfit the model. Suppose our h(θ) is :

θ0 + θ1x + θ2x2 + θ3x3 + θ4x4

Suppose we penalize and make θ3 and θ4 very small (if it is ver small then 3rd and 4th degree term will be ~ 0). Initially cost function is :

$\Large\frac{1}{2m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2 $

Now let’s try to reduce θ3 and θ4 and we can do that by simply adding these new terms to our cost function :

$\Large\frac{1}{2m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2 $ + 1000θ32 + 1000θ42

We’ve added two extra terms at the end to inflate the cost of θ3 and θ4. Now, in order for the cost function to get close to zero, we will have to reduce the values of θ3 and θ4 to near zero. This will in turn greatly reduce the values of θ3x3 and θ4x4 in our hypothesis function. Now this updated cost function will automatically reduce the value of 3rd and 4th degree parameter. When these becomes small then automatically, hypothesis function becomes quadratic and it doesn’t overfit anymore. More generally in regularization : Small values of parameters means : Simpler hypothesis and less prone to verfitting.

More Specific

Suppose in our house price prediction problem :

Features = x1, x2, x3, … , x100

Parameters = θ1, θ2, θ3, … , θ100

Out of these 100 parameters we don’t know which parameters to pick to minimize. So, we will modify our cost function to shrink all parameters by modifying our cost function :

$\Large\frac{1}{2m}$ ($\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2 + \lambda\sum_{i=1}^n\theta_j^2 )$

This is extra modification - $\lambda\sum_{i=1}^n\theta_j^2$

Here $\lambda$ is called regularization parmeter. It controls the trade of between 2 goals :

- To fit the training set well

- To keep θ small

Case 1

If $\lambda$ is very large - We will penalize all θ very highly and hence θ will be very small. Which will result in underfitting as it will fail to fit even training data.

Case 1

If $\lambda$ is very small - We will not penalize all θ at all and hence θ will be very large. Which will result in overfitting as it will fit training data very severely.

Regularization in Linear Regression

If you remember the gradient descent algorithm was :

Repeat until convergence {

θ1 = θ1 - $\alpha$ $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}).x^{(i)}$

}

Now adding the regularized parameter the algorithm will become :

Repeat until convergence {

θ1 = θ1 - $\alpha$ $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}).x^{(i)} + \frac{\lambda}{m}\theta_j$

}

After expanding the gradient descent algorithm becomes :

θj = θj(1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$) - $\alpha$ $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}).x^{(i)}$

Here 1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$ will be < 1 if we have sufficient training examples. Now since 1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$ is < 1 it will make θj smaller. Hence our regularization function has been implemented successfully.

In terms of normal equation - Our initial formula for normal equation was :

θ = (XTX)-1XTY

We wont go into detailed explanation but after applying regularization the equation will become :

θ = (XTX + $\lambda$I)-1XTY

where I is diagonal matrix with first value 0 and rest 1.

One more interesting thing about regularization in normal equation is that after adding this new term $\lambda$I, (XTX + $\lambda$I) is always invertible.

Regularization in Logistic Regression

In logistic regression our cost function was denoted by :

J(θ) = - $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m ( ylogh_\theta(x) + (1 - y)log(1 - h_\theta(x)))$

Here we will just add regularization parameter which is :

J(θ) = - $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m ( ylogh_\theta(x) + (1 - y)log(1 - h_\theta(x)))$ + $\frac{\lambda}{2m}\sum_{j=1}^{m}\theta_j^2$

Now applying this in gradient descent it will become :

θj = θj(1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$) - $\alpha$ $\Large\frac{1}{m}$ $\sum_{i=1}^m (h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}).x^{(i)}$

Which is similar to regularized linear regression. Here 1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$ will be < 1 if we have sufficient training examples. Now since 1 - $\frac{\alpha\lambda}{m}$ is < 1 it will make θj smaller. Hence our regularization function has been implemented successfully.