Introduction to Machine Learning Systems Design

ML systems design takes a system approach to MLOps, which means that we’ll consider an ML system holistically to ensure that all the components—the business requirements, the data stack, infrastructure, deployment, monitoring, etc.—and their stakeholders can work together to satisfy the specified objectives and requirements.

Before we develop an ML system, we must understand why this system is needed. Once everyone is on board with the objectives for our ML system, we’ll need to set out some requirements to guide the development of this system. Before using ML algorithms to solve your problem, you first need to frame your problem into a task that ML can solve.

Business and ML Objectives

We first need to consider the objectives of the proposed ML projects. When working on an ML project, data scientists tend to care about the ML objectives: the metrics they can measure about the performance of their ML models such as accuracy, F1 score, inference latency, etc. They get excited about improving their model’s accuracy from 94% to 94.2% and might spend a ton of resources—data, compute, and engineering time—to achieve that.

But the truth is: most companies don’t care about the fancy ML metrics. They don’t care about increasing a model’s accuracy from 94% to 94.2% unless it moves some business metrics. So what metrics do companies care about? While most companies want to convince you otherwise, the sole purpose of businesses, according to the Nobel-winning economist Milton Friedman, is to maximize profits for shareholders. For an ML project to succeed within a business organization, it’s crucial to tie the performance of an ML system to the overall business performance.

Many companies create their own metrics to map business metrics to ML metrics. For example, Netflix measures the performance of their recommender system using take-rate: the number of quality plays divided by the number of recommendations a user sees. The higher the take-rate, the better the recommender system.

Many companies like to say that they use ML in their systems because “being AI-powered” alone already helps them attract customers, regardless of whether the AI part actually does anything useful. When evaluating ML solutions through the business lens, it’s important to be realistic about the expected returns. Due to all the hype surrounding ML, generated both by the media and by practitioners with a vested interest in ML adoption, some companies might have the notion that ML can magically transform their businesses overnight.

Magically: possible. Overnight: no.

Returns on investment in ML depend a lot on the maturity stage of adoption. The longer you’ve adopted ML, the more efficient your pipeline will run, the faster your development cycle will be, the less engineering time you’ll need, and the lower your cloud bills will be, which all lead to higher returns.

Requirements for ML Systems

We can’t say that we’ve successfully built an ML system without knowing what requirements the system has to satisfy. The specified requirements for an ML system vary from use case to use case. However, most systems should have these four characteristics: reliability, scalability, maintainability, and adaptability.

Reliability

The system should continue to perform the correct function at the desired level of performance even in the face of adversity (hardware or software faults, and even human error). ML systems can fail silently. End users don’t even know that the system has failed and might have kept on using it as if it were working. For example, if you use Google Translate to translate a sentence into a language you don’t know, it might be very hard for you to tell even if the translation is wrong.

Scalability

There are multiple ways an ML system can grow. It can grow in complexity. Your ML system can grow in traffic volume. An ML system might grow in ML model count. This growth pattern is especially common in ML systems that target enterprise use cases. Whichever way your system grows, there should be reasonable ways of dealing with that growth. When talking about scalability most people think of resource scaling, which consists of up-scaling (expanding the resources to handle growth) and down-scaling (reducing the resources when not needed)

However, handling growth isn’t just resource scaling, but also artifact management. Managing one hundred models is very different from managing one model. With one model, you can, perhaps, manually monitor this model’s performance and manually update the model with new data. Since there’s only one model, you can just have a file that helps you reproduce this model whenever needed. However, with one hundred models, both the monitoring and retraining aspect will need to be automated. You’ll need a way to manage the code generation so that you can adequately reproduce a model when you need to.

Maintainability

It’s important to structure your workloads and set up your infrastructure in such a way that different contributors can work using tools that they are comfortable with, instead of one group of contributors forcing their tools onto other groups. Code should be documented. Code, data, and artifacts should be versioned. Models should be sufficiently reproducible so that even when the original authors are not around, other contributors can have sufficient contexts to build on their work. When a problem occurs, different contributors should be able to work together to identify the problem and implement a solution without finger-pointing.

Adaptability

To adapt to shifting data distributions and business requirements, the system should have some capacity for both discovering aspects for performance improvement and allowing updates without service interruption. Because ML systems are part code, part data, and data can change quickly, ML systems need to be able to evolve quickly. This is tightly linked to maintainability.

Iterative Process

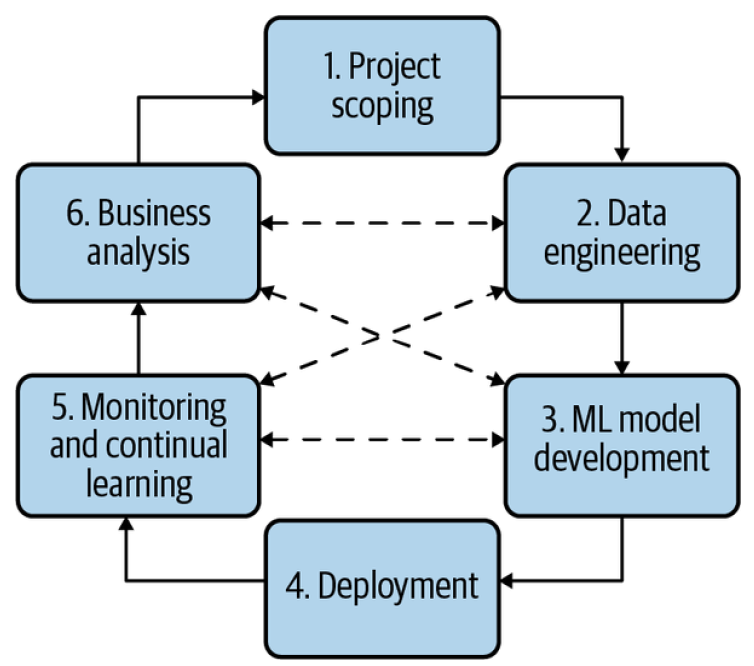

Developing an ML system is an iterative and, in most cases, never-ending process. Once a system is put into production, it’ll need to be continually monitored and updated. For example, here is one workflow that you might encounter when building an ML model to predict whether an ad should be shown when users enter a search query :

- Choose a metric to optimize. For example, you might want to optimize for impressions—the number of times an ad is shown.

- Collect data and obtain labels.

- Engineer features.

- Train models.

- During error analysis, you realize that errors are caused by the wrong labels, so you relabel the data.

- Train the model again.

- During error analysis, you realize that your model always predicts that an ad shouldn’t be shown, and the reason is because 99.99% of the data you have have NEGATIVE labels (ads that shouldn’t be shown). So you have to collect more data of ads that should be shown.

- Train the model again.

- The model performs well on your existing test data, which is by now two months old. However, it performs poorly on the data from yesterday. Your model is now stale, so you need to update it on more recent data.

- Train the model again.

- Deploy the model.

- The model seems to be performing well, but then the businesspeople come knocking on your door asking why the revenue is decreasing. It turns out the ads are being shown, but few people click on them. So you want to change your model to optimize for ad click-through rate instead.

- Go to step 1.

- Project Scoping - A project starts with scoping the project, laying out goals, objectives, and constraints. Stakeholders should be identified and involved. Resources should be estimated and allocated.

- Data engineering - A vast majority of ML models today learn from data, so developing ML models starts with engineering data.

- ML model development - With the initial set of training data, we’ll need to extract features and develop initial models leveraging these features.

- Deployment - After a model is developed, it needs to be made accessible to users. Developing an ML system is like writing—you will never reach the point when your system is done. But you do reach the point when you have to put your system out there.

- Monitoring and continual learning - Once in production, models need to be monitored for performance decay and maintained to be adaptive to changing environments and changing requirements.

- Business analysis - Model performance needs to be evaluated against business goals and analyzed to generate business insights.

Framing ML Problems

Imagine you’re an ML engineering tech lead at a bank that targets millennial users. One day, your boss hears about a rival bank that uses ML to speed up their customer service support that supposedly helps the rival bank process their customer requests two times faster. He orders your team to look into using ML to speed up your customer service support too. Upon investigation, you discover that the bottleneck in responding to customer requests lies in routing customer requests to the right department among four departments: accounting, inventory, HR (human resources), and IT. You can alleviate this bottleneck by developing an ML model to predict which of these four departments a request should go to.

Types of ML Tasks

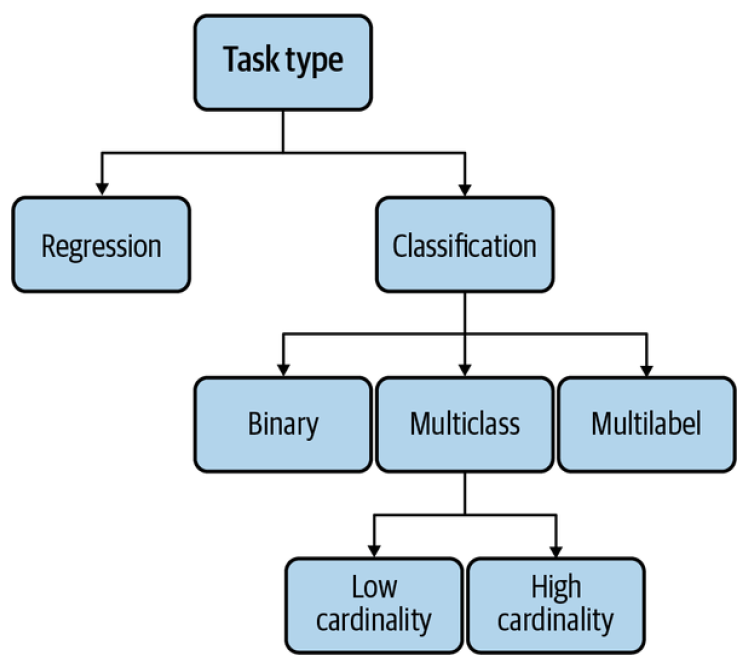

The output of your model dictates the task type of your ML problem. The most general types of ML tasks are classification and regression. Types_ML.png

- Classification VS Regression - Classification models classify inputs into different categories. For example, you want to classify each email to be either spam or not spam. Regression models output a continuous value. An example is a house prediction model that outputs the price of a given house. A regression model can easily be framed as a classification model and vice versa.

- Binary VS Multiclass classification - The simplest is binary classification, where there are only two possible classes. Examples of binary classification include classifying whether a comment is toxic, whether a lung scan shows signs of cancer, whether a transaction is fraudulent. When there are more than two classes, the problem becomes multiclass classification. Dealing with binary classification problems is much easier than dealing with multiclass problems.

- Multiclass VS Multilabel classification - When an example can belong to multiple classes, we have a multilabel classification problem. For example, when building a model to classify articles into four topics—tech, entertainment, finance, and politics—an article can be in both tech and finance. Out of all task types, multilabel classification is usually the one that I’ve seen companies having the most problems with. Multilabel means that the number of classes an example can have varies from example to example.

Changing the way you frame your problem might make your problem significantly harder or easier.

Objective Functions

To learn, an ML model needs an objective function to guide the learning process. An objective function is also called a loss function, because the objective of the learning process is usually to minimize (or optimize) the loss caused by wrong predictions. For supervised ML, this loss can be computed by comparing the model’s outputs with the ground truth labels using a measurement like root mean squared error (RMSE) or cross entropy.

Framing ML problems can be tricky when you want to minimize multiple objective functions. An objective is represented by an objective function. In general, when there are multiple objectives, it’s a good idea to decouple them first because it makes model development and maintenance easier. First, it’s easier to tweak your system without retraining models, as previously explained. Second, it’s easier for maintenance since different objectives might need different maintenance schedules. Spamming techniques evolve much faster than the way post quality is perceived, so spam filtering systems need updates at a much higher frequency than quality-ranking systems.

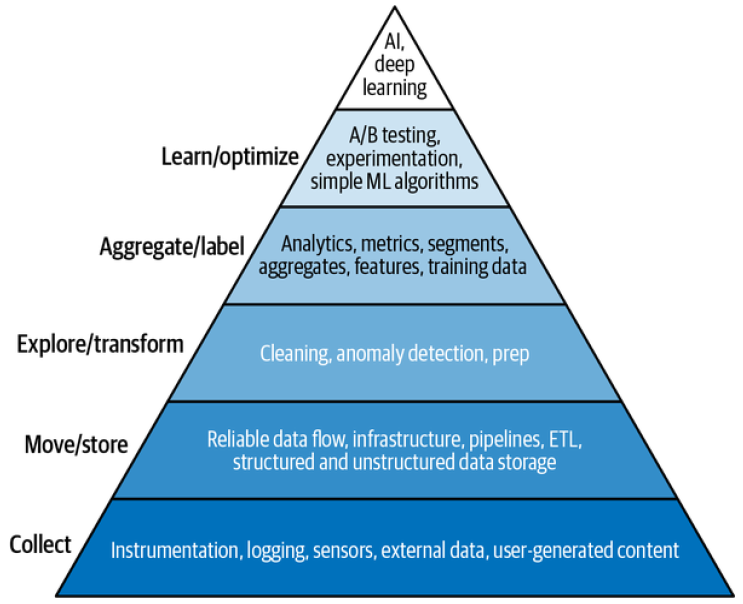

Mind Versus Data

Progress in the last decade shows that the success of an ML system depends largely on the data it was trained on. Instead of focusing on improving ML algorithms, most companies focus on managing and improving their data. Mind might be disguised as inductive biases or intelligent architectural designs. Data might be grouped together with computation since more data tends to require more computation.

Many people in ML today are in the data-over-mind camp. When asked how Google Search was doing so well, Peter Norvig, Google’s director of search quality, emphasized the importance of having a large amount of data over intelligent algorithms in their success: “We don’t have better algorithms. We just have more data.”

Regardless of which camp will prove to be right eventually, no one can deny that data is essential, for now. Both the research and industry trends in the recent decades show the success of ML relies more and more on the quality and quantity of data. Models are getting bigger and using more data.

Even though much of the progress in deep learning in the last decade was fueled by an increasingly large amount of data, more data doesn’t always lead to better performance for your model. More data at lower quality, such as data that is outdated or data with incorrect labels, might even hurt your model’s performance.